Farm Management Could Take a Lesson From Baseball

If you love statistics, then you probably love baseball. Where else can you know with certainty that your starting pitcher has a propensity to throw more fast-balls than breaking pitches to left-handed batters at home during afternoon games in June under sunny skies with a slight north-west wind? While this is a bit of a tongue-in-cheek poke at the nauseating volume of stats that originate from the game of baseball, such statistics and the subsequent use of those statistics have real world applications.

I’m sure many of you have seen the movie Moneyball. (I’m sure most of you have because I watch VERY few movies, and even I’VE seen it.) As the story unfolded, there many beautiful examples of how the management team of the Oakland Athletics baseball club used statistics to improve their team. In this specific scene (I can’t recall who the player was) Assistant GM Peter Brand (played by Jonah Hill) explicitly instructs the player to “take the first pitch” during every at bat. The reason was because through the use of statistics, and tracking the data, management knew that this player got on base more often when he took the first pitch. In the movie, it worked, and this player’s on-base-percentage increased almost immediately.

What would have happened had this team’s management not had, or used, such important information? The player may have been released, sent down to the minors, or traded to another team, the manager (bench boss) may have been fired. Spread those “uninformed decisions” across the entire roster, and failure is sure to proliferate.

Livestock and dairy farms have been heading down the road to improved data management for years already. Average daily gain is not a new concept in beef operations. Robotics in dairy parlors bring a whole new level of data management. In conversation with a farm family that is investigating the benefits of robotics in a dairy parlor, I’ve learned that through RFID technology and a robot milker, they will be able to record and monitor milk volumes and milking frequency (a cow can come to the robot for milking whenever she chooses.) The management team can then compare results across the herd to determine which cow(s) is producing more or less than others cows under similar conditions. Informed decisions can then be made.

Grain farms having been catching up in recent years. With field mapping technology we can create yield maps; overlay that with crop inputs applied and we can tell which areas of each field are more profitable than others.

But that is way ahead of where most of the industry is generally at. By and large, many farm operations still don’t know the true profitability of a specific crop on their whole farm, let alone any given field.

The progression of profitability management, which requires stringent data management, begins at the crop level, advances to the field level, and reaches the pinnacle at the acre level.

Imagine:

- determining which crops to exclude or include in your rotation by clearly understanding which crop makes you money and which one doesn’t;

- deciding which fields to seed to which crop, or even which fields to renew with the landlord or which to relinquish based on profitability by field;

- controlling your investment in crop inputs by acre to maximize your profit potential of the field, the crop, and your whole farm.

None of this is new. All the farm shows and farm publications dedicate significant space to all the tools and techniques available in the marketplace to facilitate such gathering of useful information. Equipment manufacturers and data management companies have invested enormous volumes of time and capital into creating tools and platforms to collect and manage your data. But like any tool, its value is only apparent when it is used to its full potential.

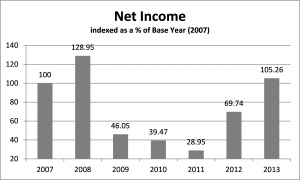

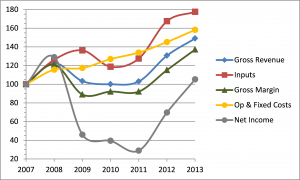

Almost all of the farms I speak with achieve greater clarity in the profitability of each crop in their rotation. I have a 13,000ac client that has taken several major steps toward measuring profitability by field. They have found that the extra work required to COLLECT this information is minimal. The extra work required to MANAGE this information is greatly offset by the benefit of clearly understanding that some of their rented land is just not profitable under any crop. Do you suppose they are looking forward to relinquishing some $90/ac rented land that just isn’t profitable enough to pay that high rent?

Direct Questions

Which of the crops in your rotation are profitable? Which are not? How profitable are they? Do they meet your expectations for return on investment?

Collecting the data is easy; managing the data takes some effort. What effort are you prepared to invest to make the most informed decisions possible?

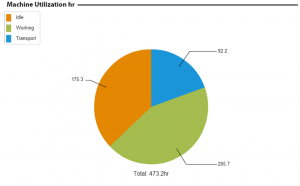

How are you fully utilizing the tools available to you? If you’re not, why would you have them?

From the Home Quarter

Baseball collects gargantuan volumes of data on players, plays, games, and seasons. Much of it seems useless to laypeople like us, but to those who make their living in “the grand old game,” the data is what they live and breathe by. Agriculture should be no different. We should be creating consecutive series’ of data on our fertility, seed, chemicals, equipment, human resources, etc, for each year we operate, for each field we sow, for each person in our employ. Management cannot make informed decisions without adequate and accurate information. Now, with all the tools, techniques, and support readily available to help farmers collect adequate and accurate information, the last piece that may be missing is, “What to do with all that data?” While it can be boring to analyze data and create projections, I can assure everyone that the most profitable farmers I know all share one common habit: they spend time on their numbers, they know their numbers, and they make informed decisions based on those numbers.

You collect the information. I can help you use it. I’ll make tractor calls (as opposed to house calls) during seeding…as long as you have a buddy seat. Call or email to set up a time.