In Issue #1 of Growing Farm Profits Weekly, we introduced how nurturing your business was one of

many critical factors that can affect your business success. This week, we’ll look deeper at nurturing

your business and how to leverage this often overlooked aspect of owning and operating a successful

enterprise.

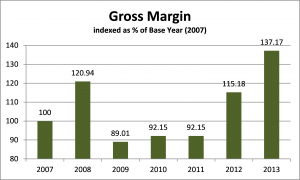

Increasing wealth is the goal of any business, and only a healthy business can deliver accordingly. And

how you view wealth can be as unique as you are. The obvious answer is “profit at the bottom line,” or

“strong equity,” but some will argue that wealth is “discretionary time.” How do you define “wealth?”

Give it some thought; it will provide clarity in how you run your business.

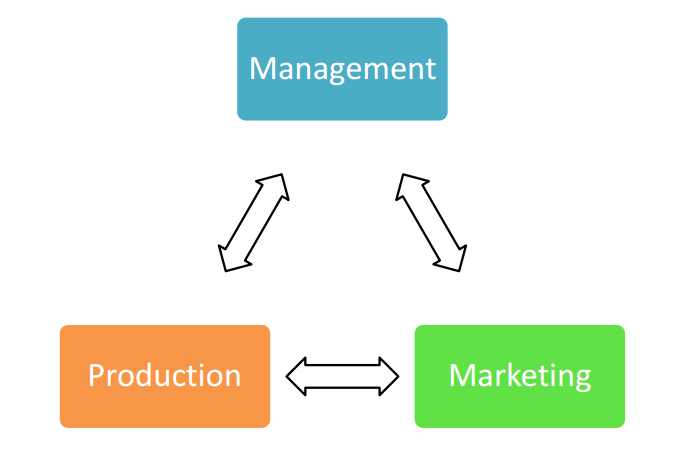

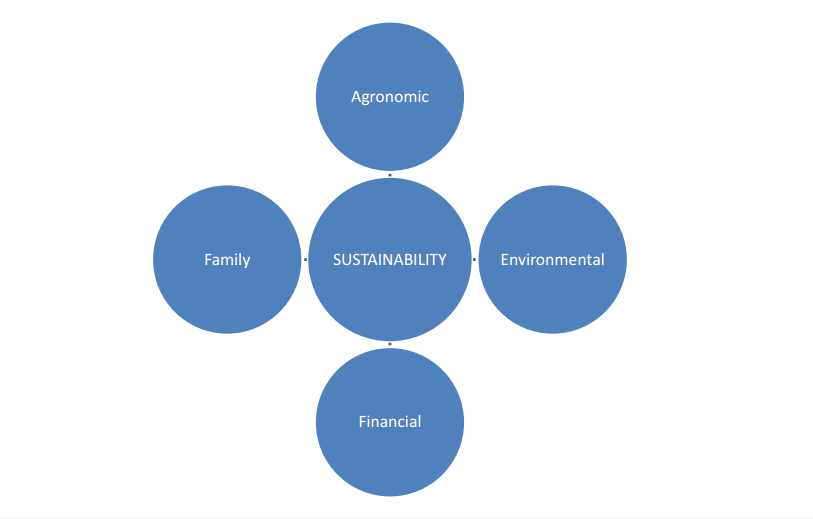

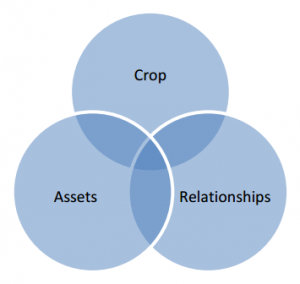

There is a healthy ratio of nurturing that applies to 3 key aspects of your business:

Crop

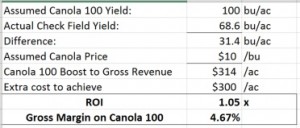

As discussed in the previous issue of Growing Farm Profits Weekly, your crop gets substantial amounts

of your attention because you know that investing significantly in your crop will grow you a better crop.

And a better crop leads to better marketing opportunities, which lead to stronger cash flow and higher

margins, which lead to profit. Simple as that? If only…

Assets

Yes, this means the tractors and combines, the trucks and trailers, the sprayers and swathers…the equipment on the farm needs to receive adequate nurture; these are the tools of your trade, and they need to perform when you need them. This is why you service regularly, send equipment into the shop for a certified tech to go through it in the off-season, and consistently use recommended operating procedures to ensure you minimize the risk of downtime.

But how much time do you spend nurturing your “other” assets?

Your HUMAN ASSETS (ie. your family and hired staff) require nurturing too. Unlike a piece of equipment

that runs the same whether you yell at it & operate with great disregard or if you treat it like a treasure,

your human assets often require a specialized approach. Just like you can relate and react better or

worse with certain people and their approach, your HUMAN ASSETS will also respond better or worse to

your approach. And if you view your human assets with the same regard you view your equipment, or

with less esteem than you give your equipment, then you’d better take a long hard look at your business

because it will be vastly different in a year or two.

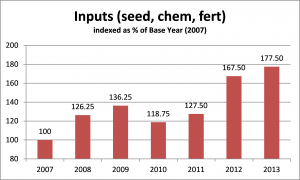

If we consider the cost of owning/leasing and operating your farm equipment, it’s a safe bet you’d be in

the range of $40-$90/ac. Yes, that’s a big range, but there are big differences in each farm’s expense

management (we’ll tackle this in a future issue.) Please note this does not include capital outlay for the

purchase price. The cost of ownership/lease and operation looks at operating costs (fuel, oil, repairs,

etc.) lease costs, and “real” depreciation (not necessarily what CRA allows you to claim as a non-cash

expense.) We also consider custom work when calculating machinery cost per acre. Now that we’ve

established that your iron has a significant cost, why would anyone consider putting a $15/hr operator

in it? In one hour, you’ve paid an operator $15 to run equipment across upwards of 25ac or so that can

carry a machinery cost of $500-$1,000. Again, if you view your human assets as dispensable, this isn’t a

surprise in your line of thinking. But then it also shouldn’t be a surprise when that same operator isn’t

too concerned about stopping to rectify those plugged hoses on the air-drill.

If you’ve spent time building specific processes around HR management, you already recognize the need

to nurture your human assets. Congratulations, you’re on your way to ensuring the future success of

your business. Some processes you will want to implement are:

- Recruiting, interviewing and selection

- Performance management

- Wages and incentives

There are many more items for this list, but we’ll save that for a future issue.

Relationships

While grain farming in North America is a commodity based industry, successful operation of your

business requires your adeptness at managing several key relationships. These relationships cover the spectrum from your professional advisors all the way to the part-time weekend counter staff at the equipment dealer.

I’ve seen some who give their least regard to the relationship with their accountant. True story; they see

the accountant as a “necessary expense” in order to file the “necessary tax forms.” Sadly, there are

many farmers out there who share that view. They do not recognize the importance of evaluating

business results against expectations or projections. I suppose these are also the businesses which do

not make business plans or projections.

How about service relationships? It’s easy to commoditize the grain buyer, the inputs retailer, or the fuel

supplier because there is always competition vying for your business. But if you don’t nurture the

relationship with your fuel supplier, what are the odds you’ll get that urgent May long-weekend

delivery?

Do service relationships extend to your staff? Do you pay them to provide you and your business with a

service, or are they integral members of your farm team? What do they need? What motivates them?

Why are they working for you and not somewhere else? If you don’t know the answers to these

questions, you’ve got 4 more days this week to find out…get on it!

Direct Questions

How do YOU define “wealth?”

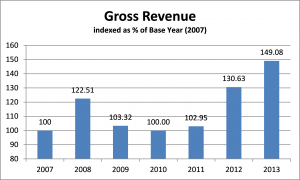

Are you getting the most out of your crop? By that I mean “are you maximizing the most efficient

processes” available to produce your crops? It’s not about the highest yield at the coffee-shop; it’s about

gross margin (yet another future issue.)

Have you calculated the ROI on nurturing your human assets relative to the ROI on your iron assets?

What processes and procedures have you implemented to support your efforts to nurture your human

assets?

Ask yourself how you value the relationship you have with the following:

- Agronomist

- Business Advisor

- Accountant

- Banker

- Lawyer

- Commodity Markets Advisor

- Equipment Dealer

- Inputs Retailer

- Fuel Supplier

- Family

- Staff

Is there one way you can strengthen each relationship this month?

Are you nurturing one aspect of your farm to the detriment of another? Why? Have you calculated the

net cost of this practice?

From the Home Quarter

We invest our resources in a manner that we expect to provide us with a return. And no matter if that return is tangible or intangible, it all creates the net benefit to our business: positive or negative.

You’ll notice I will rarely refer to the weather in this writing because we cannot control the weather. As a

business advisor, I focus on what we can control. For example, how do we invest and allocate our

resources: financial, intellectual, human, equipment, and most importantly, time. I believe in Alan

Weiss’ theory that “wealth is discretionary time.”

For any business owner to achieve maximum discretionary time, he/she must recognize what they do

best, and get help with the rest. Business owners must nurture their business in such a manner that

maximizes ROI, because as Alan Weiss says, “real wealth is discretionary time, but money is the fuel for

that wealth.”

Don’t get so caught up in earning money that you have no wealth.

Profit is not a swear word.

Time is the most precious, non-renewable, intangible resource we could ever spend. Treat it as such.

Growing Farm Profits™ provides topical and pragmatic business management tips and tools for primary

producers in Canadian agriculture.