Why the Canola 100 Challenge is So Wrong

Announced two years ago around this time, the Canola 100 challenge baits farmers into taking part in a “moonshot”: an attempt to produce a verified canola yield of 100 bushels per acre. It isn’t that efforts to increase yield aren’t a good thing, because they are. But by what means are we attempting to achieve these yields?

This “contest” may be virtuous in spirit, but it overlooks the not-so-old adage that “better is better before bigger is better.” That applies to this argument too.

The rationale behind my position is supported in this Western Producer article that describes a farmer’s chase of this moonshot, throwing everything including the kitchen sink at his crop in an attempt to cash in on the Canola 100 prize. (Spoiler alert: it failed miserably.) This particular attempt can be summarized in this quote from the article:

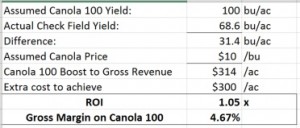

The fertility program cost $300 per acre more than what was done to the check field but yielded only 70 bu. per acre, which was 1.4 bu. per acre more than the check field.

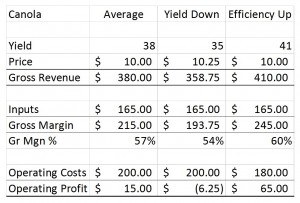

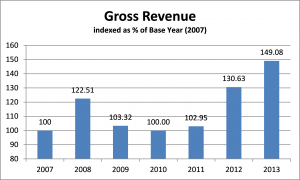

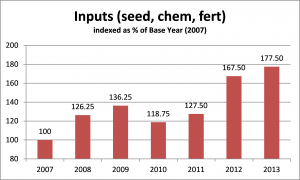

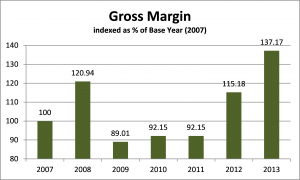

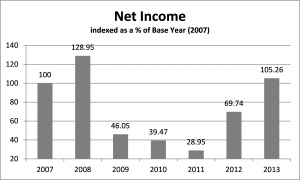

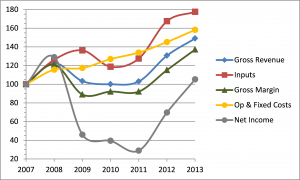

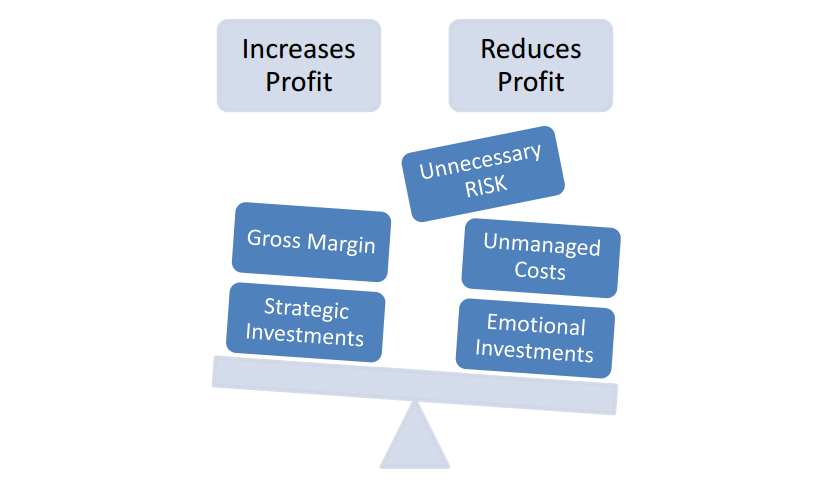

The driving factor behind efforts to maximize yields should be ROI (Return on Investment) and Gross Margin. Doing so would focus on maximum economic yield, not maximum production yield. There’s something about that pesky law of diminishing returns that gets overlooked when trying to shoot for the moon…

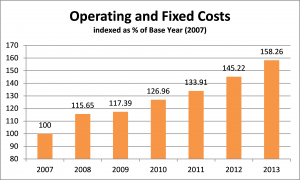

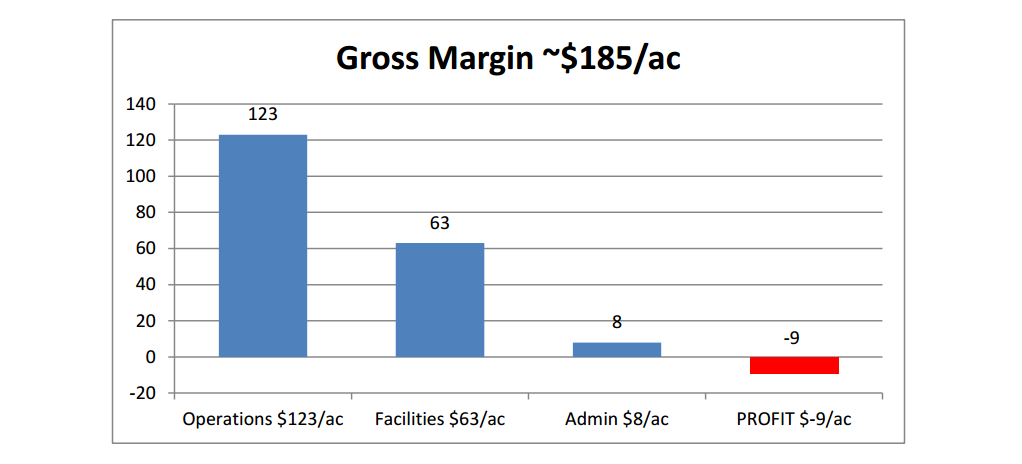

If maximum economic yield is the target, then Gross Margin is the focus. How that gross margin is achieved is up to each producer, but make no mistake about where the focus needs to be. In my experience, minimum gross margin, that is gross revenue less seed, chemicals, and fertilizers, at MINIMUM needs to be 65% to sustain the business. High cost operations need greater gross margin to cover all those costs.

To put that in reverse, if 35% of your gross revenue can go to crop inputs, then each $1.00 invested into inputs should return $2.86 in gross revenue. To apply this to the example above, the “extra $300 per acre” in fertility should have delivered $858/ac in gross revenue. If Canola was $10/bu, that’s nearly 86 bushels per acre above the check field.

Let’s push the argument harder: if the example above actually hit 100 bushels per acre, and acknowledging the control field yielded 68.6 bu/ac, the gross margin on the Canola 100 plot was $14 per acre, or about 4.67%.

This is IF the 100 bushel yield was achieved…and face it, $14 gross margin doesn’t pay many bills; in fact, it wouldn’t even buy the fuel for the contest plot.

To Plan for Prosperity

Make no mistake about the messaging here: as a producer of commodities, you need the bushels!!! But do not lose sight of the fact that as a producer of commodities, your only chance of remaining sustainably profitable is to produce at the lowest cost per unit. Period. Chasing maximum yield at a 1:1 ROI won’t get it done.

1. What is your historical gross margin?

2. What are your operating and overhead costs?

3. Know these to be able to plan for maximum economic yield.