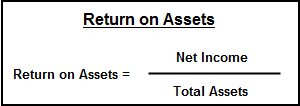

ROA (Return on Assets)

Return on assets, or “ROA” as we’ll refer to it, is an often overlooked financial metric on the farm. Partly, I think it is because there is a culture in agriculture that places too much emphasis, even “romanticizes” the accumulation of assets (namely land, but mostly equipment.) This doesn’t necessarily bode well for ROA calculations. But the greater reason ROA isn’t a regular discussion on the farm, in my experience, is because it is not understood.

The math is simple to understand, so when I say “ROA is not understood,” I mean that the significance of ROA, and its impact, is not appreciated.

Return on Assets is a profitability measure. Its key drivers are operating profit margin and the “asset turnover ratio.” ROA should be greater than the cost of borrowed capital.

Let’s ask the question: “When calculating ROA, do we use market value or cost basis of assets in the denominator?” The simple answer is “BOTH!”

Do two calculations:

1) using “cost” to measure actual operational performance;

2) using market value to measure “opportunity analysis” which is a nice way of saying “could you invest in other assets that might generate a better return than your farm assets?”

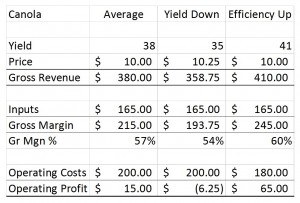

Operating profit margin is calculated as net farm income divided gross farm revenue, and is a key driver of Return on Assets.

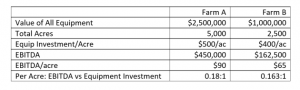

The asset turnover ratio (also a key driver of ROA) measures how efficiently a business’ assets are being used to generate revenue. It is calculated as total revenue divided by total assets. The crux of this measurement is that it has a way of showing the downside of asset accumulation. The results of this calculation illustrate how many dollars in revenue your business generates for every dollar invested in assets. While there is no clear benchmark for this metric, I’ve heard farm advisors with over 3 decades experience share figures that range from 0.25 to 0.50. This means that for every dollar of investment in assets, the business generates 25-50 cents of revenue (NOTE, that is REVENUE not PROFIT).

If assets increase and revenue does not, the asset turnover figure trends negatively.

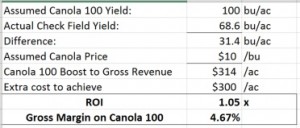

If revenue increases and profit does not, the operating profit margin trends negatively.

Increasing revenue alone will not positively affect ROA. “Getting bigger” or “producing more” alone without increasing profit does not make a difference. If you recall: “Better is better before bigger is better…”

To Plan for Prosperity

As you will find in many of these regular commentaries, the financial measurements described within are each but one of many practical tools to be used in the analysis of your business. Return on Assets cannot be used on its own to determine the strength or weakness of your operation. But used in combination with other key metrics, we can determine where the hot issues are, and how to fix them so that your business can maximize efficiency, cash flow, and profitability.