This opinion piece was published on farmfutures.com on April 3, 2017. Titled What’s Your Farm’s Survival Plan, the author, Mike Wilson, describes how farm income in the US Mid-west is falling and thus challenging working capital to remain at adequate levels. As you have read here, and on my Twitter feed (if you follow me) is how borrowing is becoming more difficult for US Mid-west farmers. I’ve posed the question several times is “Who thinks this can’t happen here” (in western Canada?)

Wilson lays out five practices that farmers can use to improve their chances of keeping a good relationship with their lender. Before discounting the suggestion by saying, “Yeah, well it’s different in Canada,” give it a read and appropriate consideration. Unless, or course, you believe it can’t happen here…

The graphic is a screen capture of an excerpt of the article from the Farm Futures website. The text has been copied below, with my comments following each one:

The graphic is a screen capture of an excerpt of the article from the Farm Futures website. The text has been copied below, with my comments following each one:

What do lenders think when you walk through the door? If you do these five things, financing shouldn’t be much of an issue:

- Lenders will work with farmers who can communicate and execute a plan, whether it’s for marketing, cash flow, or both.

*KG: we’ve discussed here many times over the years how important it is to communicate with your lenders who typically don’t like surprises. And while we’ve been preaching for years the value of planning, there is a key word in the statement above that, if ignored, makes planning the useless task so many farmers feel it is: execute.

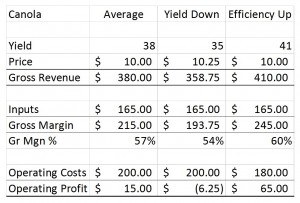

2. Understand breakeven analysis and keep family living expenses low. Look for that extra dime in your marketing plan. Watch for opportunities to keep yields above average. A lot of that is just paying attention to details.

*KG: break-even analysis is one part of it. Utilizing Unit Cost of Production (UnitCOP) is critical not only to your break even analysis, but also your marketing strategy. It provides a built in sensitivity analysis to both prices and yields. It will clarify the importance of “that extra dime” in your marketing plan. It provides a level of detail that most farms still don’t employ in decision making…

3. Lenders need to know how you will pay them back. You can walk into their office, tell them about the 50 acres that just came up for sale next to your farm and expect to be approved — but that’s not how it works. They need to see that you’ve done your homework. They need to see your accurate balance sheet, income statement, accrual income adjustments, and other key financials. They need to see the numbers before they can pull the trigger.

*KG: Bankers make informed decisions; “they need to see the numbers before they can pull the trigger.” If the numbers are absent, it’s a hard stop. If the numbers are questionable, meaning that the credibility of the figures come into question, it’ll also be a hard stop. Several years ago, I witnessed a would-be borrowing get slammed by several quality bankers because the borrower provided sloppy info that was unverifiable. Lenders won’t make a decision to proceed without quality information; neither should you.

4. Be conservative with your money. “This will be a learning experience,” says Dan Gieseke, Missouri Farm Service Agency farm loan chief. “Many have not been through a tough time. They need to be conservative now, so they can be ready to take advantage of opportunities when they come along.”

*KG: The best time to be conservative with your money was 5 years ago. The next best time is right now. My old pal Moe Russell says, “If you are greedy in the good times, you’ll be on your knees in the bad times.” While shiny paint often feels better than a big bank balance, it is that bank balance (the life-blood of your business: working capital) that will not just help you survive the bad times, it will propel you through them; it’ll maybe even help you thrive during those bad times when your competitors are on their knees…

5. Use records to do analyses. “My fear is that farmers don’t use them,” says Purdue economist Freddie Barnard. “In the ’80s, we got beat up. But the tools to do the analyses then were not out there. There are tools now. Just use them, and try to make informed decisions.”

*KG: there are so many tools available, so much information available, that I would have a hard time arguing against someone who is admitting that “it’s overwhelming.” It is. While I would empathize, I wouldn’t accept that as an excuse. There are many qualified people in this industry who are ready, willing, and able to help you sort through the overwhelm, and establish a strategy to develop and implement a process to get you to a working level of comfort with data management, analysis, and decision making.

To Plan for Prosperity

“Do what you do best, and get help for the rest” is a cornerstone of my advisory work. If none of the five points above strike a chord with you because you don’t know how to do them, or don’t like doing what they suggest, then take a moment to ask yourself if the five points above are actually important to you.

If they are, but you’re not sure where to start, then start by picking up the phone and calling someone for help.

If they’re not, then good luck to you. You’re going to need it.

Your business, your family, and your legacy are too important to be left to chance.