Last week, I was emailed an article by Rob Carrick of The Globe and Mail. Carrick writes about Canada’s borrowing binge; no not our federal government deficit and growing debt, but Canada’s household debt. Let’s see how it applies not only to household debt, but farm debt.

**NOTE: Carrick’s article is below in italics, with my comments inserted in bold.

“It’s getting harder to see anything but a messy ending for Canada’s household debt binge.

This isn’t the beginning of a lecture on reducing your borrowing. It’s more a resigned observation of human behaviour. You can warn people to act now to avoid a potentially bad outcome in the future, but they’re not likely to do anything unless they see trouble dead ahead.

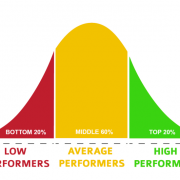

The second quarter of 2016 was a vintage moment in debt accumulation. Incomes rose, as Statistics Canada puts it, “a weaker-than-normal” 0.5 per cent, while household debt growth clocked in at 2 per cent. This is the Canadian way – keep debt levels growing ahead of gains in income.

On two counts, this is bad personal finance. Your household spending flexibility is negatively affected in the short term (you have less money to save, for example), and you’re more vulnerable to financial shocks ahead, such as rising interest rates or an economic decline that kills jobs. Clearly, most people aren’t worried about these risks.”

What risks make you worried about your debt load? Can you control them (ie. fusarium, sclerotinia, excess moisture, interest rates, commodity prices?)

“The explanation starts with the fact that we live in a world in which conditions for borrowing are as good as they can ever be. Interest rates are low and the economy, while tepid, is producing enough jobs to prevent unemployment from becoming a big issue.

In the field of behavioural finance, there’s a term called “recency bias” that describes what’s happening here. People are looking at recent events and projecting them into the future indefinitely. So far, it’s working. We’ve had low rates and a slow-moving but stable economic for years now, and there’s no sign of imminent change.”

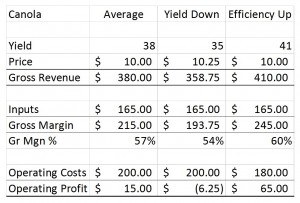

“Recency bias” describes the not so distant thinking that canola wouldn’t go below $10/bu, meaning that “$10 was the new floor” (circa 2012.) There were many other behaviors and attitudes that came with that thinking. How quickly forgotten are the years of poor quality and inconsistent yields…

“Under these conditions, there’s no reason to heed the repeated warnings from the Bank of Canada, economists, finance ministers, credit counsellors and personal-finance columnists about the dangers of taking on more debt. And so, the ratio of household debt to disposable income hit a record 167.6 per cent in the second quarter, up from 149.3 per cent in the second quarter of 2008.”

Is there a reason to heed the warnings from ag economists, management advisors, and creditors about the dangers of taking on more debt….? Depends how much debt you currently carry.

“Recent warnings about debt levels give us an idea of what could happen if there are any economic shocks ahead. The credit-monitoring firm TransUnion said earlier this week that more than 700,000 people would be financially stressed if rates went up by a puny quarter of a percentage point, and as many as one million would be affected if rates went up by a full point.

The Canadian Payroll Association recently surveyed 5,600 people and almost 48 per cent of them said it would be tough to meet their financial obligations if their paycheque was delayed even by a week. Almost one-quarter doubted they could come up with $2,000 for an emergency expense in the next month.

These reports highlight some of the risks of the borrowing binge we’ve been on for the past several years, but not all. Decades down the road, we may find that people didn’t save enough for retirement in the 2010s because they were so burdened by debt. Student debt levels might rise in the future because parents weren’t able to help with tuition costs.”

An interest rate sensitivity test would answer this question for your particular operation. But more important that interest rates, which in reality are unlikely to experience any significant increase in the short-medium term, is income volatility. The debt payments won’t change, but a farm’s ability to make those payment will. If the debt payments can only cash-flow when yields and price are at high points, there is trouble ahead.

“That second-quarter data from Statscan show clearly how deaf people are to warnings about the dangers of debt. In the worst three-month period since the recession, economic output fell by an annualized rate of 1.6 per cent.

The reaction of employers to this economic dip can be seen in the fact that income growth was weaker than normal in the second quarter. Consumers barely flinched, though. They’re impervious not only to warnings about the dangers of high debt levels, but also to periodic bouts of economic volatility like we saw in the second quarter. Only a big shock will get their attention.

There’s no point trying to forecast when a shock will happen, but what we do know for sure is that the financial and economic conditions of today will change. We remain in an adjustment phase following the financial crisis and recession late in the past decade and it’s far from clear what the new normal will be.

Things could get better for the economy, or they’ll get worse and jobs will be vulnerable. Either way, people are going to have to make stressful adjustments that they could have avoided by reducing debt today. This could get messy.”

From the Home Quarter

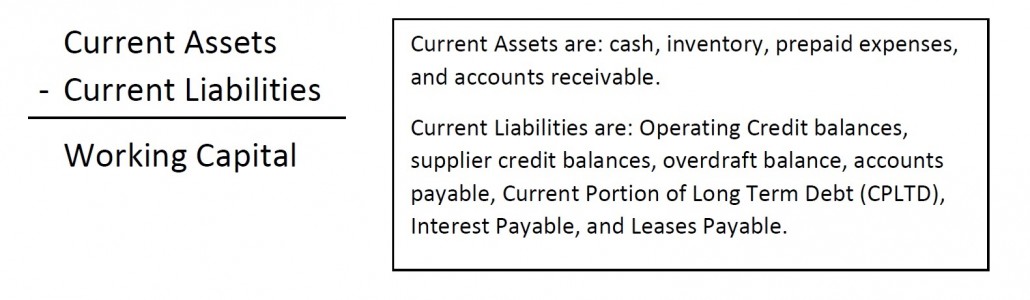

It has been well documented that farm debt in Canada is high. In the next breath, there is all kinds of spin added to the argument such as stating current debt in 1982 dollars so as to compare to the carnage that was beginning 34 years ago. Not to try to deflate the validity of constant dollar comparisons, but the cold hard reality is that existing debts, today’s liabilities, need to be paid back. Compare the situations all we like, describe how “things are different now;” either way, no matter how you slice it, current farm incomes need to pay present day debts.

So when I hear of lentil yields often coming in at half of expectation, when I hear of wheat and durum crops again decimated by fusarium, when I hear of malt barley crops grading as feed because of all the rain, I can only hope that those farms who experience such production results this year are not over-leveraged. Is this a hint of “the big shock” Carrick wrote about, as it would apply to agriculture? Or is that big shock something already on the radar like China slamming the door on Canadian canola that doesn’t meet spec?

The borrowing binge at the consumer level, as Rob Carrick wrote about, could have drastic implications on the Canadian economy; his words also apply to agriculture. We could be in for a rough ride, “this could get messy” as Carrick wrote.

Sage words from a 30+ year farm advisor: “Take your worst net income over the last 10 years and measure it against today’s debts. How do you feel?”

If you don’t feel good from that experiment, please call me or email for strategies to help ease the discomfort.