Soil Testing Season

This is the time of year when soil probes all over the prairie are taking samples of the soil that provided the crop in the current year and will provide another crop next year. It’s an annual “check-in” to see what’s left.

It was the same about a year ago. We check what nutrient levels remain after harvest, consider what crop will perform best in each field next year, and begin to apply appropriate nutrients (following the 4R’s of Fertility: Right Source, Right, Rate, Right Time, and Right Place) in fall and/or in spring. The crop get’s sown, produce get’s harvested, and we check the soil again. Based on what we started with, what we added, and what the crop used to through the growing season, we compare to what is left in the soil to evaluate how efficient our fertility program was.

If it wasn’t as efficient as it could have been, we examine the effects on our production (moisture, heat, disease, insects, etc.) and we examine our own role in the process by questioning if the seed tool did a good enough job; how about the sprayer? Often time we use weather as the justification to acquire bigger, newer equipment to “get the job done faster.”

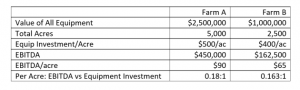

What if the entire industry, not just the progressive managers but the entire industry, used that same methodology in analyzing profit and cash flow? It might look something like this:

This is the time of year when spreadsheets all over the prairie are being used to tally up the performance of the business over the last growing season. We start with the working capital we had after last harvest, consider what crop will perform best based on your crop rotation and market outlook, and begin to project input costs and yield & price for each crop. We enter expected operating and overhead costs into a projection, and convert those projections to “actuals” as the year progresses. Once harvest is complete, we evaluate working capital again.

If profitability and cash flow was insufficient to meet expectations, we examine if operating costs stayed within budget or not (and why), we examine if overhead costs were projected correctly or if we let both operating and overhead “get away” this year. What did we not foresee? What did we properly plan for? Did we market appropriately?

The practice of soil testing compliments crop and fertility planning. These are crucial steps to take to create the most efficient plan. Remember, you need to produce at the lowest cost per unit possible. Period. Hard Stop.

The practice of checking financial performance is similar to keeping score. It would be awfully tough to know what adjustments need to be made during the game (growing season) without knowing the score along the way.

To Plan for Prosperity

It’s been said by agronomists that soil testing is “seeing what’s in the bank account” and they carry on in supporting that analogy by stating that no one would write a cheque without knowing what the bank balance is first. Sadly, there any many people who do both: write cheques without knowing what’s in the bank and plant crops without knowing what’s in soil. One won’t break you, the other could.

Knowledge is power. Knowledge comes from management. Management requires measurement. Test your soil (financial performance), because if you don’t measure it, you can’t manage it.

**Side note: the photo is from my farming days, and provides a glimpse into the soil I used to farm. I found it interesting to so clearly see the A, B, and C horizons in a single core. **